Apr 12, 2024

A Pirate's Discretion: Modeling Differences Between Legal and Illicit Anime-Streaming Communities

The paper takes three data sets representing the legal anime-streaming community (Crunchyroll), the illegal anime-streaming community (AniWave), and the whole, non-sectioned anime community (MyAnimeList), and studies the intersection of all three sources across key feature variables. Using LASSO regression and random forest trees, two powerful machine learning models, it then predicts the commercial success of shows on both the legal and illegal streaming sites and highlights the different variables significant to each platform

Abstract

Market segmentation allows businesses to divide their target market into distinct sections and fine-tune their commercial approach to each one. In the anime-streaming market, however, these distinctions are often blurred, particularly over the distinction of the legality of streaming means—either of legal or illicit streaming sites—attenuating market insights that stakeholders might expect to successfully guide internal and customer-facing decisions. This paper proposes and tests the hypothesis that differences between the two kinds of streaming sites and their user bases are statistically and practically significant, refactoring the way entertainment leaders select and support shows for broadcast and streaming in the anime market.

To do this, the paper takes three data sets representing the legal anime-streaming community (Crunchyroll), the illegal anime-streaming community (AniWave), and the whole, non-sectioned anime community (MyAnimeList), and studies the intersection of all three sources across key feature variables. Using LASSO regression and random forest trees, two powerful machine learning models, it then predicts the commercial success of shows on both the legal and illegal streaming sites and highlights the different variables significant to each platform. The best-performing model on the Crunchyroll data, LASSO, achieved an r-squared of 0.494. Random forest trees, the best-performing model on the AniWave data, achieved an r-squared of 0.596. The most significant variables for the Crunchyroll data, moreover, regardless of model, are controversy (the extent to which AniWave and Crunchyroll ratings disagree about any show) and the number of episodes in a show; for AniWave, the show’s success according to MyAnimeList, and again, the number of episodes.

Introduction

Japanese animation, colloquially referred to as “anime,” has in recent decades spread far beyond the borders of the single island nation to the shores of countries both near and to the opposite side of the globe. Out of all television sub-genres, anime ranked third highest in global demand share, claiming 4.74% of international watch time (Parrot Analytics, 2021)—an impressive feat of outsized popularity, given Japan’s 1.53% share of the world population (Worldometer, 2024).

Indeed, nowhere else is anime’s international influence more palpable than in the United States, with franchises like Pokémon, Dragon Ball, and Naruto hemmed and stitched to both casual streetwear and luxury brands (Sinha, 2023), adored by Hollywood stars like Michael B. Jordan and Keanu Reeves (Barnes 2023)—even making its way to Capitol Hill when Hillary Clinton, in her 2016 presidential election campaign, famously declared before a Virginia rally how she hoped to galvanize young voters to “Pokémon Go to the polls” (White, 2016).

The numbers quantify anime’s penetrating influence in everyday American life: In 2022, the anime market reached an evaluation of 25.8 billion USD and is projected to reach 62.7 billion USD by 2032, growing with a CAGR of 9.4% (DataHorizzon Research, 2023). Among all US Netflix users, moreover, 74% have watched at least one anime show and 27% watch anime content every day (Lindner, 2023).

However, while streaming platforms like Netflix offer one point of entry into the world of anime, they were not the first nor the only medium. Due to licensing difficulties and lagging investments by American television networks, particularly in the late 1900s when anime was first introduced to the United States, the main way that American anime fans watched their favorite shows was through “fansubs”—English-subtitled shows independently produced by fans fluent in Japanese (Stone, 2018). These fansubs were then distributed pro bono across the internet, ignoring copyright laws and bypassing the capital-heavy, arduous process of licensing negotiations (Sevakis, 2012).

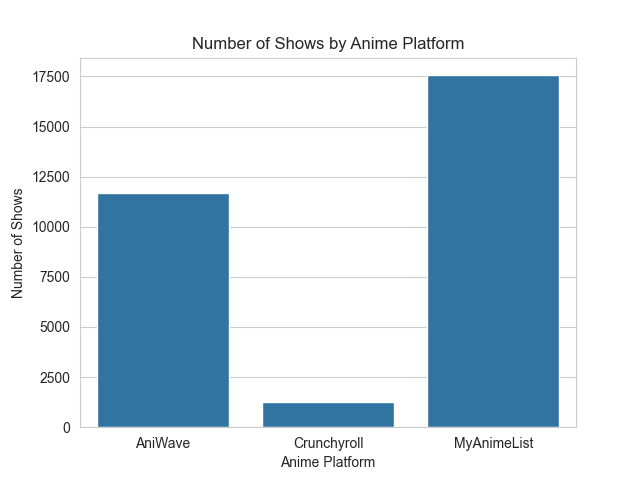

Even as legal means of anime access have exponentially grown through the 2000s, much of the original grassroots culture remains on these pirating sites, preserving a sense of nicheness and community among older fans. Moreover, while streaming platforms have made tremendous progress securing licensing rights to old and simulcast shows alike, many titles remain inaccessible by sites like Netflix and Hulu—even by anime-specialty sites such as Crunchyroll, America’s preeminent anime provider. The following visualization highlights disparities between the number of shows available on Crunchyroll, AniWave, an anime-pirating website, and MyAnimeList, an anime database documenting every type of anime media commercially available.

Although functioning as an anime database rather than a streaming service makes this feat much easier, MyAnimeList boasts the record of 17562 shows, followed by AniWave’s 11675 shows—66.48% of the MyAnimeList collection. The drop from AniWave’s second to Crunchyroll’s third is even steeper, however, with only 1255 shows on the legal streaming platform. During anime’s nascent experience in the United States, perhaps pirating has become a necessary yet liminal evil—first, as the only way fans can watch certain anime shows, and second, to demonstrate enough demand for anime to attract the attention and capital of American entertainment leaders. Similarly, this was how foreign media like Charles Dickens’ novels rose to stardom in the United States—through publishing companies that, unfettered by toothless copyright laws, ripped off from the English author and disseminated his work at a discounted price (The Dickens Society, 2023).

Looking forward, however, as the US streaming infrastructure matures and anime is increasingly merged into the mainstream, the salutary effects of pirating shrink, all the while its costs persist and gradually eclipse the dimming benefits: In 2021, The Content Overseas Distribution Association estimated anime-piracy losses to be 15 billion USD, over five times the estimated losses from only two years earlier in 2019. While the pandemic-era lockdowns certainly contributed to this uptick and rates might have fallen since the national reopening, nonetheless, the expanded pirating infrastructure (in websites, supply chains, etc.) continues through the present, exacerbating the already enormous losses far beyond the size they would have been bar lockdowns (The Content Overseas Distribution Association, 2023, as cited in Peters, 2023).

Thus, it appears facile to study the anime market as though all participants were an average of what are likely two distinct types of anime fans: First, the type that consumes their anime content through illegal streaming services, and second, the type that tolerates advertisements or pays to legally watch their shows. This study then sets out to accomplish two things: To accentuate key differences between legal and illegal streaming users, and with that knowledge, to highlight advantages illegal sites might have over their legal competitors and how legal sites might adapt to win over more of the anime market. Moreover, broadening our understanding of both communities can help legal sites predict show success—both for their current user base and unreached segments of the anime market claimed by pirating services.