Dec 22, 2023

The Plague of Complaint: How Network Effects Explain the Breakdown of Consumer Sentiment Forecasts

The network effects of public, visible reactions to COVID disposed consumers toward complaint and pessimism but left private, lesser-visible behaviors untouched and consistent with economic realities.

Overview

Now several years beyond the inception of COVID-19 lockdowns and economic recession, the United States has returned, slowly but surely, back to prior levels of output and activity. Yet despite the many reasons for optimism in today’s economy, consumer sentiment lies depressed, languishing in an antiquated period of six feet apart, forehead thermometers, bulging bins over-stuffed with toilet paper and packages of masks.

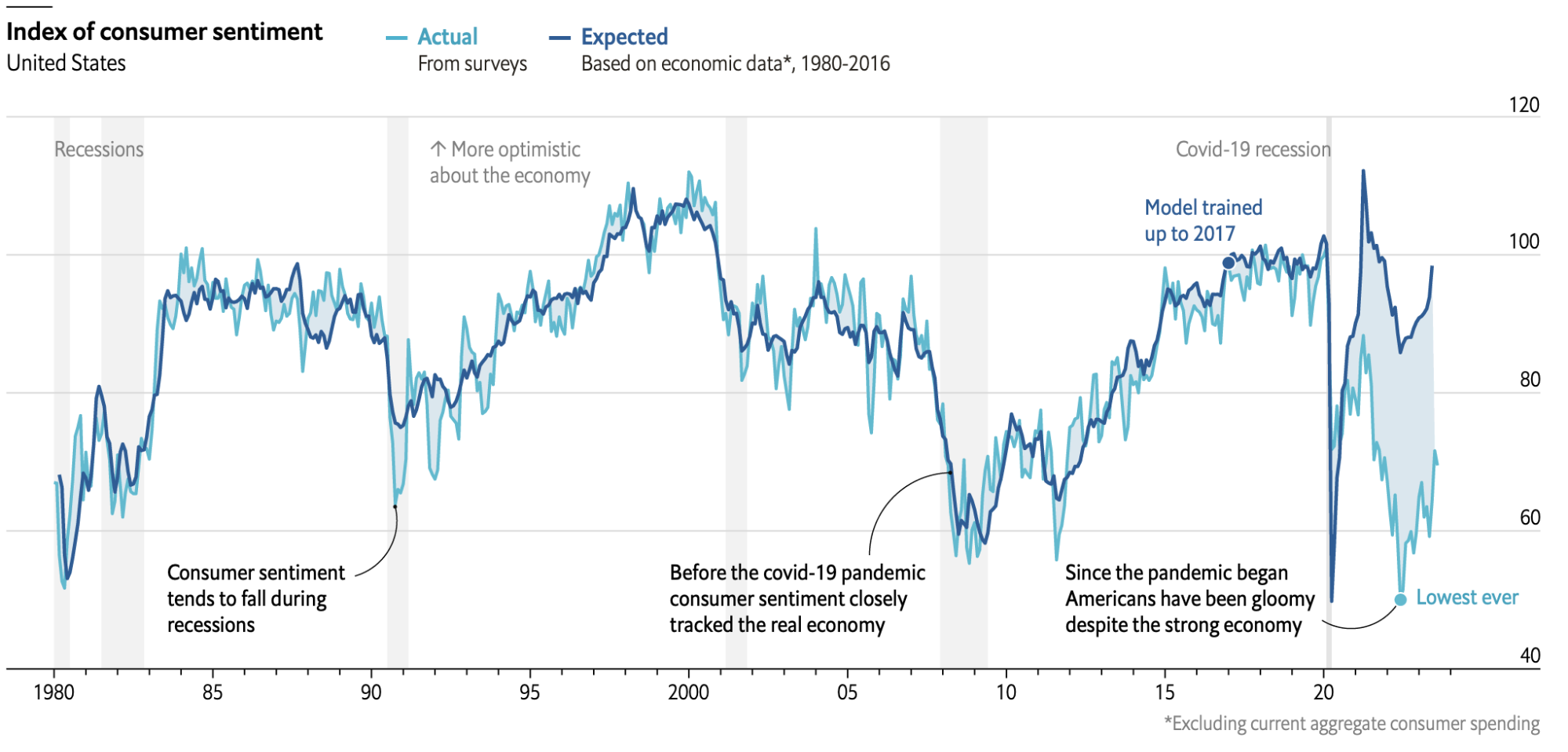

Since 1946, the University of Michigan has kept an ongoing 5-question survey of consumer sentiment, asking each month a new representative sample of 600 Americans about their household financial conditions and thoughts/predictions about economic trends—questions such as “Would you say that you (and your family living there) are better off or worse off financially than you were a year ago?” and “Generally speaking, do you think now is a good or bad time for people to buy major household items?” Using survey responses, university researchers have accurately forecasted consumer spending sentiments for over forty years, up until the pandemic-marked year of 2020 when actual consumer sentiments plummeted beneath predicted sentiments produced by models trained on economic data from 1980-2016, as shown in the following chart provided by The Economist (“The pandemic has broken a closely followed survey of sentiment”):

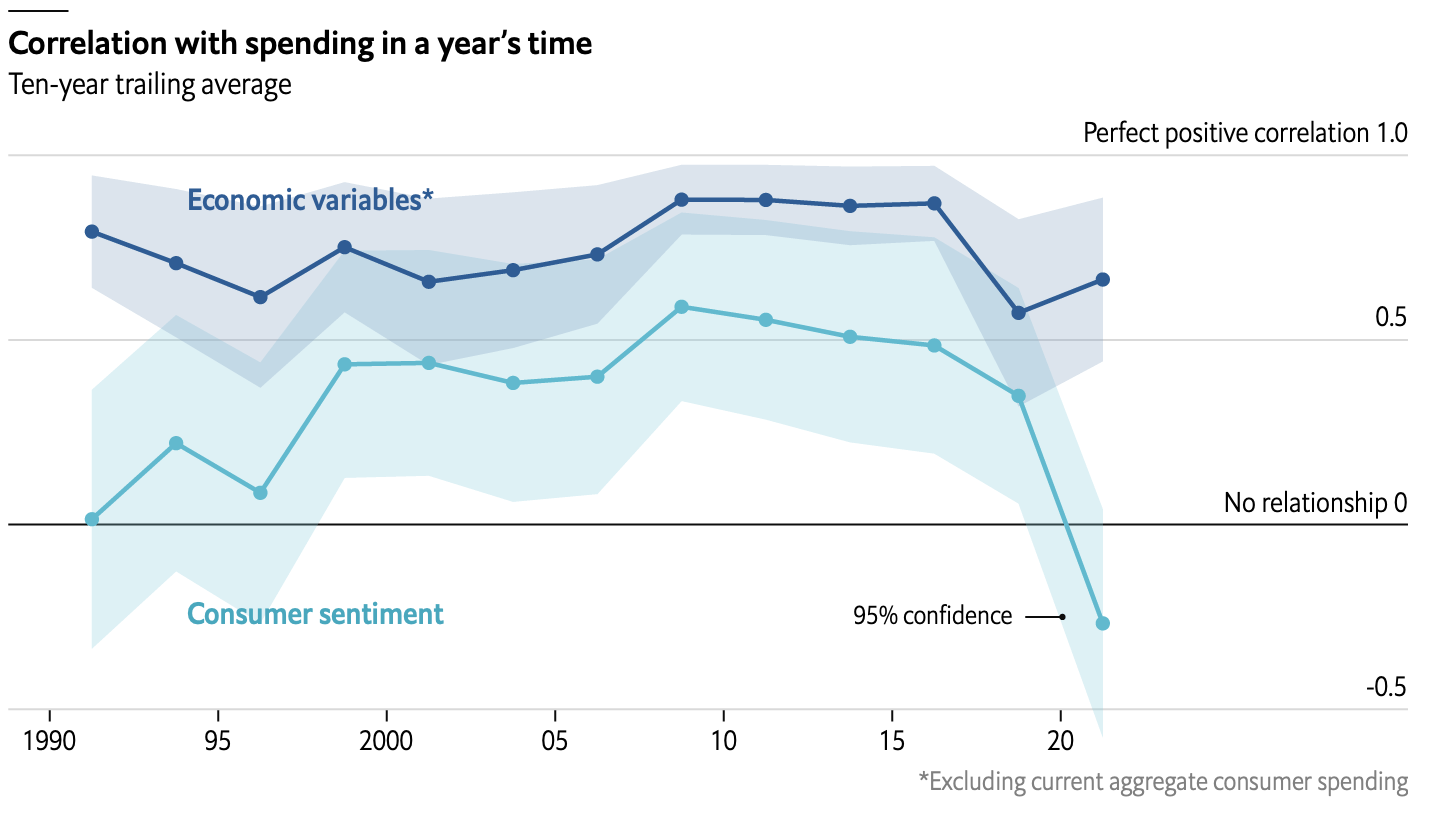

In other words, given the same economic conditions, consumers post-pandemic have far bleaker economic outlooks than their pre-pandemic counterparts. Indeed, while consumer sentiment, like economic variables, was once correlated with consumer spending, that link has since malfunctioned. Another chart from The Economist illuminates this discontinuity:

Beyond 2020, consumer sentiment appears to have a negative correlation with consumer spending: The more positively consumers feel about their financial security and prospects, the correlation suggests, the less they are likely to spend; and so it appears, how consumers reportedly feel about financial realities clashes with how they act regarding their finances, as measured in spending. Though consumers may bleakly respond to Michigan’s sentiment polling, their actions in the exchange of dollars and swipes of credit cards reveal what they truly believe.

What about the pandemic era explains this cognitive dissonance between belief and behavior? A naive approach might credit the pandemic-induced financial depression. However, since 1946, there has been a slew of many slumps and even crises—most recently before the pandemic, the 2008 Housing Crisis/Great Recession—through which consumer sentiment remained trustworthy. But fundamentally, how would any economic depression explain this inversed relationship between sentiment and spending, as appears to be the case post-pandemic? Something more visceral and psychological seems to have affected the American consumer.

While the COVID-19 pandemic might have been uniquely devastating, it would be facile to address this sentiment-spending divergence as a wholly monetary issue. Rather, this paper highlights a pandemic of complaint spread over conduits of internet connectivity, examining how the network effects of public, visible reactions to COVID disposed consumers toward complaint and pessimism but left private, lesser-visible behaviors untouched and consistent with economic realities.