Dec 08, 2023

The Opportunity Cost of Crime: Identifying Key Factors of and Solutions to the U.S. Recidivism Problem

By building a model to predict recidivism, we hope to identify those most likely to reoffend and highlight factors that contribute to recidivism, allowing policymakers to effectively target root problems that affect genuine change.

Overview

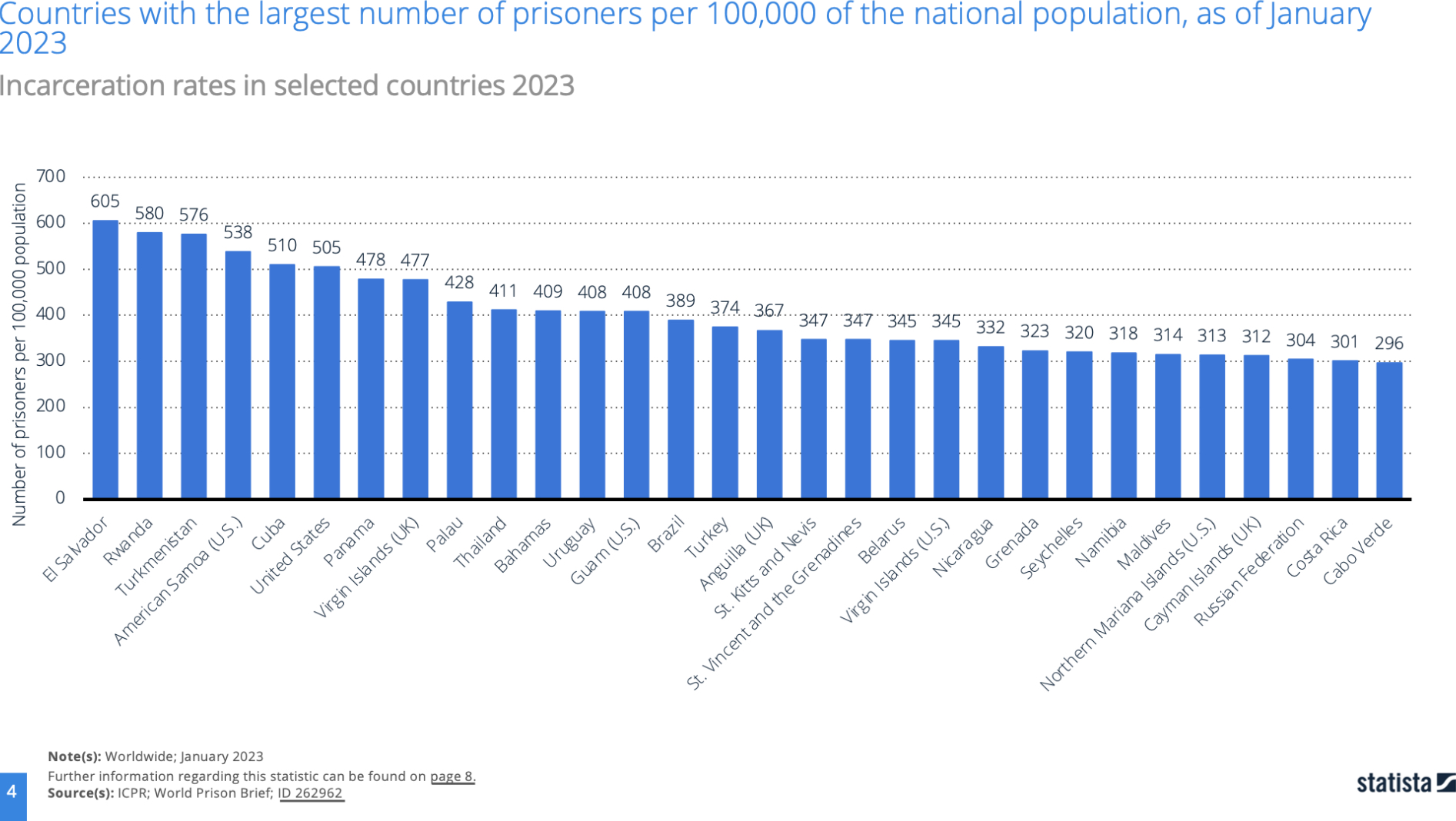

The United States, although economically, culturally and martially eminent among other major world powers, bears a paradoxical mark of shame: Ranked sixth seed, trailing close behind totalitarian Cuba, the United States has one of the highest incarceration rates in the world with a rate of 531 prisoners per 100,000 of the national population in the year 2023 (“Most prisoners per capita by country 2023”).

While this statistic might not shock relatively young Americans, it is a sharp increase from what those alive before the 1980s may remember, when incarceration rates were one-fifth—roughly 1 in 1000—of the current ~5-in-1000 proportion. Yet, while incarceration rates have risen, violent crime rates have followed the opposite trend, from its 1990 peak of 758 crimes per 100,000 of the national population to a 2022 level of 370 crimes per 100,000—over a 50% decrease (“Reported violent crime rate in the U.S. 2022”). And while the United States can boast in a moderately low crime rate compared to peer countries, the incarceration expense that it pays—both in terms of penitentiary maintenance fees and the count of freedomless inmates—to support such a rate is far greater than comparable nations.

This single statistic only scratches the surface of the complex network of life-altering decision-making that is the United States justice system—of coercive plea bargains and steep bail prices and decentralized, patchwork case reporting that shrouds courts and law enforcement behind a shadowy veil. Rather than entangle ourselves in the Kafkaesque business of court reform, we look past the system and to the prisoners, highlighting factors that might put them before a judge and jury—for the first or even second and third time. In this paper, we look at recidivism.

About Recidivism

Along with its uniquely high incarceration rate, the United States’s recidivism rate is equally as surprising, with 44% of released prisoners returning to penitentiaries in a single year—and even more within two and three years (“Recidivism Rate by State 2023”). On the other hand, the United States has also some of the world’s longest prison sentences, ranking first, 40.6 years, for homicide-related sentences, 6 years more than Mexico’s second-place 34.2 years (Warren). Indeed, a 2021 meta-analysis of 116 studies found that “custodial sanctions”—prison and other forms of confinement—”have no effect on reoffending or slightly increase it when compared with the effects of noncustodial sanctions such as probation” (Petrich et al. #).

Simply increasing penalties for crime is a well-proven strategy for failure. That is not to suggest that prisons and law enforcement should be abolished, as has become vogue in the aftermath of horrific police brutality cases, but rather to suggest that if we can make sentences more effective, even supportive of the convicted—if we can bring down the 44% rate of prisoners reoffending in just one year—we can drastically reduce the count of Americans confined behind bars without even broaching problems of the court system.

Thus, the goal of this paper is twofold: By building a model to predict recidivism, we hope to first identify those most likely to reoffend, informing where to focus support rather than penalty, and second, to highlight factors that contribute to recidivism, allowing policymakers to effectively target root problems that affect genuine change.